Introduction GBV Yeisa

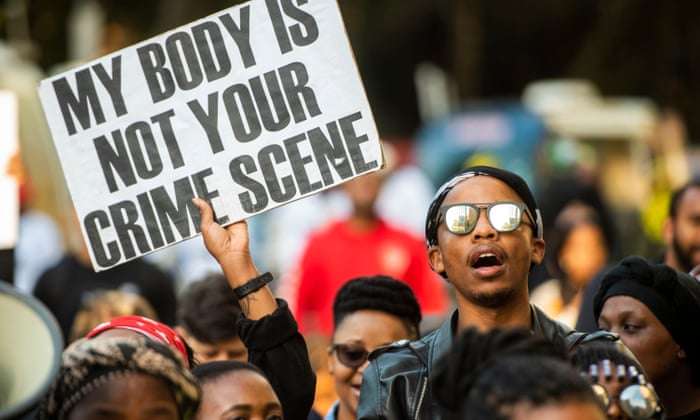

Gender-based violence (GBV) is a profound and widespread problem in South Africa, impacting on almost every aspect of life. GBV (which disproportionately affects women and girls) is systemic, and deeply entrenched in institutions, cultures and traditions in South Africa.

This introduction will explore what GBV is and some of the forms it takes, examine GBV in South Africa, and begin to explore what different actors are doing to respond to GBV.

What is gender-based violence?

Gender-based violence (GBV) is violence that is directed at an individual based on his or her biological sex OR gender identity. It includes physical, sexual, verbal, emotional, and psychological abuse, threats, coercion, and economic or educational deprivation, whether occurring in public or private life.

GBV occurs as a result of normative role expectations and unequal power relationships between genders in a society.

There are many different definitions of GBV, but it can be broadly defined as “the general term used to capture violence that occurs as a result of the normative role expectations associated with each gender, along with the unequal power relationships between genders, within the context of a specific society.”

The expectations associated with different genders vary from society to society and over time. Patriarchal power structures dominate in many societies, in which male leadership is seen as the norm, and men hold the majority of power. Patriarchy is a social and political system that treats men as superior to women – where women cannot protect their bodies, meet their basic needs, participate fully in society and men perpetrate violence against women with impunity

Forms of gender-based violence

There are many different forms of violence, All these types of violence can be – and almost always are – gendered in nature, because of how gendered power inequalities are entrenched in our society. GBV can be physical, sexual, emotional, financial or structural and can be perpetrated by intimate partners, acquaintances, strangers and institutions.

The forms of GBV include violence against women and girls, violence against LGBTI people, intimate partner violence, domestic violence, sexual violenceand indirect (structural) violence.

Structural violence is described as violence that is built into structures, appearing as unequal power relations, and consequently, as unequal opportunities affecting certain groups, classes, genders or nationalities of people. Political and social norms change can address structural violence.

Intimate partner violence (IPV)

Intimate partner violence is the most common form of GBV. It includes physical, sexual, and emotional abuse and controlling behavior’s by a current or former intimate partner or spouse. Intimate partner violence can happen in heterosexual or same-sex couples. For more information on intimate partner violence and domestic violence, read this WHO brief.

Violence against women and girls (VAWG)

GBV is disproportionately directed against women and girls. For this reason, you may find that some definitions use GBV and VAWG interchangeably, and in this article, we focus mainly on VAWG.

Violence against LGBTI people

However, it is possible for people of all genders to be subject to GBV. For example, GBV is often experienced by people who are seen as not conforming to their assigned gender roles, such as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and/or intersex people

Domestic violence (DV)

Domestic violence refers to violence which is carried out by partners or family members. As such, DV can include IPV, but also encompasses violence against children or other family members.

Sexual violence (SV)

Sexual violence is “any sexual act, attempt to obtain a sexual act, unwanted sexual comments or advances, or acts to traffic, or otherwise directed, against a person’s sexuality using coercion, by any person regardless of their relationship to the victim, in any setting, including but not limited to home and work.” [6]

Indirect (structural) violence

Structural violence is “where violence is built into structures, appearing as unequal power relations and, consequently, as unequal opportunities.

Structural violence exists when certain groups, classes, genders or nationalities have privileged access to goods, resources and opportunities over others, and when this unequal advantage is built into the social, political and economic systems that govern their lives.”

GBV in South Africa

Societies free of GBV do not exist, and South Africa is no exception.

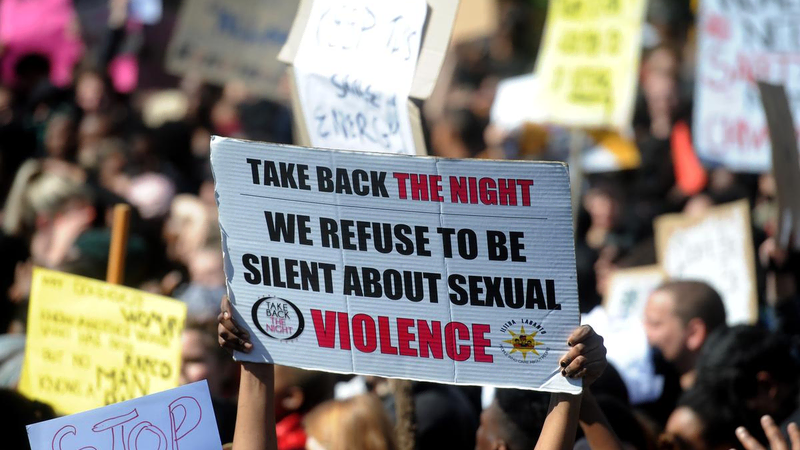

Although accurate statistics are difficult to obtain for many reasons (including the fact that most incidents of GBV are not reported it is evident South Africa has particularly high rates of GBV, including VAWG and violence against LGBT people.

Population-based surveys show very high levels of intimate partner violence (IPV) and non-partner sexual violence (SV) in particular, with IPV being the most common form of violence against women.

- Whilst people of all genders perpetrate and experience intimate partner and or sexual violence, men are most often the perpetrators and women and children the victims.

- More than half of all the women murdered (56%) in 2009 were killed by an intimate male partner.

- Between 25% and 40% of South African women have experienced sexual and/or physical IPV in their lifetime.

- Just under 50% of women report having ever experienced emotional or economic abuse at the hands of their intimate partners in their lifetime.

- Prevalence estimates of rape in South Africa range between 12% and 28% of women ever reporting being raped in their lifetime.

- Between 28 and 37% of adult men report having raped a women.

- Non-partner SV is particularly common, but reporting to police is very low. One study found that one in 13 women in Gauteng had reported non-partner rape, and only one in 25 rapes had been reported to the police.

- South Africa also faces a high prevalence of gang rape.

- Most men who rape do so for the first time as teenagers and almost all men who ever rape do so by their mid-20s.

- There is limited research into rape targeting women who have sex with women. One study across four Southern African countries, including South Africa, found that 31.1% of women reported having experienced forced sex.

- Male victims of rape are another under-studied group. One survey in KwaZulu-Natal and the Eastern Cape found that 9.6% of men reported having experienced sexual victimisation by another man.

Drivers of GBV

Drivers of GBV are the factors which lead to and perpetuate GBV. Ultimately, gendered power inequality rooted in patriarchy is the primary driver of GBV.

GBV (and IPV in particular) is more prevalent in societies where there is a culture of violence, and where male superiority is treated as the norm. A belief in male superiority can manifest in men feeling entitled to sex with women, strict reinforcement of gender roles and hierarchy (and punishment of transgressions), women having low social value and power, and associating masculinity with control of women.

These factors interact with a number of drivers, such as social norms (which may be cultural or religious), low levels of women’s empowerment, lack of social support, socio-economic inequality, and substance abuse.

In many cultures, men’s violence against women is considered acceptable within certain settings or situations – this social acceptability of violence makes it particularly challenging to address GBV effectively.

In South Africa in particular, GBV “pervades the political, economic and social structures of society and is driven by strongly patriarchal social norms and complex and intersectional power inequalities, including those of gender, race, class and sexuality.

Impact of gender-based violence

GBV is a profound human rights violation with major social and developmental impacts for survivors of violence, as well as their families, communities and society more broadly.

On an individual level, GBV leads to psychological trauma, and can have psychological, behavioural and physical consequences for survivors. In many parts of the country, there is poor access to formal psychosocial or even medical support, which means that many survivors are unable to access the help they need. Families and loved ones of survivors can also experience indirect trauma, and many do not know how to provide effective support.

Jukes and colleagues outline the following impacts of GBV and violence for South Africa as a society more broadly:

- South African health care facilities – an estimated 1.75 million people annually seek health care for injuries resulting from violence

- HIV – an estimated 16% of all HIV infections in women could be prevented if women did not experience domestic violence from their partners. Men who have been raped have a long term increased risk of acquiring HIV and are at risk of alcohol abuse, depression and suicide.

- Reproductive health – women who have been raped are at risk of unwanted pregnancy, HIV and other sexually transmitted infections.

- Mental health – over a third of women who have been raped develop post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which if untreated persists in the long term and depression, suicidality and substance abuse are common. Men who have been raped are at risk of alcohol abuse, depression and suicide.

Violence also has significant economic consequences. The high rate of GBV places a heavy burden on the health and criminal justice systems, as well as rendering many survivors unable to work or otherwise move freely in society.

A 2014 study by KPMG also estimated that GBV, and in particular violence against women, cost the South African economy a minimum of between R28.4 billion and R42.4 billion, or between 0.9% and 1.3% of gross domestic product (GDP) in the year 2012/2013. [21]

What do we do?

South Africa is a signatory to a number of international treaties on GBV, and strong legislative framework, for example the Domestic Violence Act (DVA) (1998), the Sexual Offences Act (2007) and the Prevention and Combatting of Trafficking in Human Persons (2013) Act”.

Response services aim to support and help survivors of violence in a variety of ways. Prevention initiatives look at how GBV can be prevented from happening.

Whilst international treaties and legislation is important it is not enough to end GBV and strengthen responses.

Addressing GBV is a complex issue requiring multi-faceted responses and commitment from all stakeholders, including government, civil society and other citizens. There is growing recognition in South Africa of the magnitude and impact of GBV and of the need to strengthen the response across sectors.

Prevention and Response

What works

For more information, check the page What Works in preventing GBV

Broadly speaking, approaches to addressing GBV can be divided into response and prevention. Response services aim to support and help survivors of violence in a variety of ways (for instance medical help, psychosocial support, and shelter). Prevention initiatives look at how GBV can be prevented from happening. Response services can in turn contribute towards preventing violence from occurring or reoccurring.

Responses are important. Major strides are being made internationally on how to best respond and provide services for survivors of violence. WHO guidelines describe an appropriate health sector response to VAW – including providing post-rape care and training health professionals to provide these services.

WHO does not recommend routine case identification (or screening) in health services for VAW exposure, but stresses the importance of mental health services for victims of trauma.

Need to address underlying causes

Much of our effort in South Africa has been focused on response. However – our response efforts need to be supported and complemented by prevention programming and policy development. By addressing the underlying, interlinked causes of GBV, we can work towards preventing it from happening in the first place.

SACQ: Primary prevention

Violence prevention policies and programmes should be informed by the best evidence we have available. Programmes that are evidence based are

- built on what has been done before and has been found to be effective;

- informed by a theoretical model;

- guided by formative research and successful pilots; and

- multi-faceted and address several causal factors.

Several GBV prevention programmes which have support for effectiveness have been implemented in South Africa. A summary of the prevention programmes mentioned below can be found in the South African Crime Quarterly: Primary prevention (see table on pgs. 35-38):

- Thula Sana: Promote mothers’ engagement in sensitive, responsive interactions with their infants

- The Sinovuyo Caring Families Programme: Improve the parent–child relationship, emotional regulation, and positive behaviour management approaches

- Prepare: Reduce sexual risk behaviour and intimate partner violence, which contribute to the spread of sexually transmitted diseases (STIs)

- Skhokho Supporting Success: Prevent IPV among young teenagers

- Stepping Stones: Promote sexual health, improve psychological wellbeing and prevent HIV

- Stepping Stones / Creating Futures: Reduce HIV risk behaviour and victimisation and perpetration of different forms of IPV and strengthen livelihoods

- IMAGE (Intervention with Microfinance for AIDS and Gender Equity): Improve household economic wellbeing, social capital and empowerment and thus reduce vulnerability to IPV and HIV infection

Importance to develop evidence base

At the same time, it is important to develop the evidence base further by exploring a range of other interventions that have the potential to be effective in a South African context. Many actors, including government, civil society and funders, as well as community members, are working in creative and innovative ways every day to address GBV.

For example, several civil society organisations are working with women’s groups to build their agency and empower them to address the issues that impact their lives, such as structural and interpersonal violence. Others are tackling specific drivers of GBV, such as substance abuse and gangsterism. Still others take a “whole community” approach to dealing with GBV, involving community members and leaders in the fight against violence in their communities.

Many of these interventions have not yet been formally documented, but they are nevertheless promising models which play an important role in the overall fight against GBV.

While South Africa has high levels of GBV, we are also a leader in the field of prevention interventions in low and middle income countries.

We are identifying models which work to respond to and prevent violence, and we can work on scaling those up to reach more people. At the same time, as a society, we can work together to find new ways to address GBV, building the current evidence base and responding to this national crisis.

Because of the ways in which this violence is built into systems, political and social change is needed over time to identify and address structural violence.

The root cause of gender-based violence is inequitable gender norms, let’s consider some firm actions that we can take all year long to end GBV In a patriarchal society, women can’t protect their bodies from violence, meet their basic needs and participate fully in society. Gender-based violence is a global problem with the same root cause – inequitable gender norms.

What are the forms of gender-based violence?

There are many forms of GBV. GBV can be physical, sexual, emotional, financial or structural and can be perpetrated by intimate partners, acquaintances, strangers and institutions.

The forms of GBV include violence against women and girls, violence against LGBTI people, intimate partner violence, domestic violence, sexual violenceand indirect (structural) violence.

Structural violence is described as violence that is built into structures, appearing as unequal power relations, and consequently, as unequal opportunities affecting certain groups, classes, genders or nationalities of people. Political and social norms change can address structural violence.

Intimate partner violence is the most common form of GBV. It includes physical, sexual, and emotional abuse and controlling behaviours by a current or former intimate partner or spouse. Intimate partner violence can happen in heterosexual or same-sex couples.

We know that GBV levels are high, but we don’t always have accurate statistics due to many factors, including the fact that most incidents aren’t reported.

GBV is very high in South Africa when compared to global levels. On average, one in five South African women older than 18 has experienced physical violence. Thousands of women and children are psychologically harmed by GBV and suffer long-term trauma and harm to their lives.

The main drivers as shown by the available statistics are intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. Gender-based violence permeates all structures of society – political, economic and social -and is driven by entrenched patriarchy and complex and intersectional power inequalities found in race, gender, class and sexuality.

How can we end gender-based violence?

We’ve made much progress in addressing the high levels of GBV. We are better at defining and understanding GBV. We are better at collecting data and evidence to identify and support effective interventions. We’ve seen relatively improved awareness and access to services. Despite the gains, gender-based violence is still a big problem.

So, how can we effectively address the fundamental inequalities to end GBV? An excellent starting point is recognising that women’s rights are human rights.

South Africa has a strong legislative framework and is a signatory to several international treaties on GBV. Examples include the Domestic Violence Act (DVA), the Sexual Offences Act, and the Prevention and Combatting of Trafficking in Human Persons (2013) Act”.

We urge all governments to ratify the recent ILO convention ((C190), which addresses violence, discrimination and harassment in the world of work.

16 days of Activism against GBV campaign happens from November 25 to December 10 every year. As we mark the campaign in 2019, let’s consider the actions that we can take all year long to end GBV. Maryce Ramsey, Senior Gender Technical Advisor at the US nonprofit, FHI 360 suggests the following six focus areas:

Six ways to end gender-based violence

Funding women’s full participation in civil society

Women who are active in civil society can be highly effective in influencing global, regional and national treaties, agreements and laws and in exerting pressure to ensure their implementation. More money needs to flow toward supporting women’s active participation in civil society.

Scaling up prevention efforts that address unequal gender power relations as a root cause of gender-based violence

Some programs have effectively structured participatory activities that guide the examination of gender norms and their relationship to power inequities, violence and other harmful behaviours. They work with multiple stakeholders across the socio-ecological spectrum and multiple sectors. But, we need to do a better job of evaluating these programs so we can move them from limited, small-scale pilots to larger-scale, societal-change programs.

RELATED RESOURCE: Creating a health system with 0% GBV – Lessons from LRS Meadowlands Clinic Pilot Project

RELATED RESOURCE: Our hearts are joined – Writings from LRS Letsema Project

Bringing gender-based violence clinical services to lower-level health facilities

The provision of gender-based violence clinical services has focused on “one-stop shops” at high-level facilities, such as hospitals, where all services are offered in one place. But, the majority of people who access services at high-level facilities do so too late to receive key interventions, such as emergency contraception and HIV post-exposure prophylaxis. For faster access, we should focus on bringing services closer to the community, particularly in rural areas.

RELATED ARTICLE: The issue of dignity in health facilities in South Africa

Addressing the needs of child survivors, including interventions to disrupt the gender-based violence cycle

In shelters and services for women, it is common to see children of all ages in waiting rooms or safe houses. But, it is rare to see anyone working with these children, who have experienced a traumatic event. Sometimes they are victims, but most likely they are witnesses to violence against their mothers. We lack trained professionals to work with children who have experienced gender-based violence, especially when the perpetrators are parents or other family members

.

Developing guidance for building systems to eliminate gender-based violence

There is ample global guidance on how to address gender-based violence through certain sectors, such as health, or through discrete actions, such as providing standards for shelters or training for counsellors. But, we are missing practical guidance for building the whole system from A to Z — putting laws into practice, raising awareness of services and creating budgets.

Developing support programs for professionals experiencing second-hand trauma

Burnout of professionals is a reality, and we lack qualified people to deal with survivors of GBV. When a professional suffers ‘vicarious trauma’ – the emotional residue of exposure from working with traumatised people – then they can’t be effective. Nosipho Twala, Educator and Facilita